Egypt

113: Egypt

Egypt is a country rich in history, full of spirited people seeking greater social freedoms. We visit 5,000 year-old temples to discover ancient storytelling and see how the stories of the past relate to power structures today. We visit Mina in Alexandria, an acclaimed cinematographer and passionate director; and we explore the role of filmmaking during the Arab Spring revolution.

Where Were You at 33?

Name: Mina Nabil

Place: Alexandria, Egypt

Age at Filming: 32

Personal logline: An Alexandrian DP-turned-director navigates his way through a colorful world in post-Arab Spring Egypt.

Directed by Mina: “The Book Of The Entry” (2011), “Away From The Heat” (2012), “Sedhom” (2013), “The Cheerful Giver” (2019), “Venice: This Is Not A Painting” (2020), “A Window Of Time – Lockdown Diaries” (2020), “I Am A Script Girl” (2026)

Follow Mina: www.minanabilfilms.com

Mina’s Instagram: @its_mina_nabil

Mina’s Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/minanabil

Mina’s Bio:

Mina is a director, DP, and producer from Alexandria with a Bachelor’s Degree in Cinema. He is one of the co-founders of Fig Leaf Studios. As a cinematographer, his clients include Google, Facebook, and UNAIDS. He has participated in the 2014 Documentary Campus Berlin, Beirut Talents 2015, the 2018 Film Independent Fellow Doc Lab, and was a nominee in 2016 for the Robert Bosch Stiftung film Prize at Berlinale and Los Angeles. Mina has screened his work at Cannes, Berlinale, and Venice. Mina mentors at the Cinedelta Documentary School in Alexandria.

About Wael Omar

Wael Omar is an Egyptian director and producer who lives in Cairo. After earning his MA in film arts in 2005, Omar shot his short documentary “State of Emergency” as part of the Democracy 76 Project, a series of short documentaries. His work aired on BBC Storyville, Al Arabiya, France 3 and ITVS as well as being screened at many international film festivals. In 2008, Omar co-founded Middle West Films, an incubator and co-production house for feature films.

Cinema of Egypt

Early Lumiere films were shown in 1896 at the Alexandria Stock Exchange of Toussoun Pasha; and the first footage shot by an Egyptian was filmed in Alexandria at the Mosque of Abul-Abbas al Mursi in 1907.

Egypt’s most internationally recognized filmmaker also hails from Alexandria: Yussef Chahine.

Born in Alexandria in 1926, Chahine’s film career spans 6 decades and over 40 feature films. Chahine’s long and prolific career can be seen as a wonderful time-capsule of Egyptian society and how it changed (or sometimes did not change) over the decades from regime to regime.

What I love about Chahine’s films is that he shows you slices of society, in what feels like very realistic representations, fully drawn out characters, and though he made so many films, each of his films feels different. Watching Chahine’s repertoire of films from earliest to latest feels like you’re taking a tour of Egypt; through different landscapes of both Upper and Lower Egypt, to different time periods. As Egypt grew, so too did Chahine as a filmmaker and storyteller. He is both proud and critical of his heritage and both elements subtly shines through his films.

The first Chahine film I watched was “The Blazing Sun” from 1954 and it was love at first sight. This was Egyptian born Omar Sharif’s breakout film (followed up by a stellar performance in Chahine’s 1956 “Dark Waters”). Omar Sharif became widely known in Hollywood for his starring roles in “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Dr. Zhivago” and “Funny Girl.” His acting career spanned over 60 years.

In “The Blazing Sun,” Sharif plays the young, hunky Ahmed, the over-achieving son of peasant farmers who manages to successfully grow the #1 sugar cane crop of the season, beating out his father’s boss, the “Pasha.” This means that for the first time ever, the company will buy their crop from the peasants rather than from the rich governor of the land, or Pasha.

This film, shot in gorgeous black and white, compellingly deals with Egyptian class-struggles head on. After all, at the time of release, we’re two years into the new monarchy-free Egypt, where the government initiates land redistribution and agricultural reform policies.

In the film, the peasants are thrilled and celebrate. The Pasha, however, is greedy and wants to destroy the peasants’ crops, which he does with the help of his underling, Riad, his nephew. But the greed doesn’t stop there: the Pasha plots to destroy anyone who gets in his way, including Ahmed’s father, who is framed for the murder of a Sheik. (“Sheik” means a learned man, a distinguished elder of sorts.). Meanwhile, Ahmed and the Pasha’s daughter, who used to play together when they were kids, are in love. The daughter helps Ahmed to clear his father’s name (posthomously, as he is already tried, convicted and hung for the crime he did not commit) only to learn that her own father is not the man she thought he was.

All of the action takes place near Luxor and several scenes were filmed in Karnak Temple, Luxor Temple and at the Valley of the Kings. Hollywood also shot a few films around Luxor, including, the James Bond flick, “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977) and the film adaptations of Agatha Christie’s book, “Death On The Nile,” originally released in 1978 directed by John Guillermin. Decades later, Kenneth Branagh directed a remake of “Death On The Nile,” released in 2022.

The cinema of the 1930s to 1960s, when Egypt was considered the “Hollywood of the Orient,” is considered Egypt’s Golden Age. The films produced during this period rivaled that of the cinema of Europe and America being made at the same time.

In early Egyptian cinema, once sound was introduced, music and cinema formed a perfect marriage in the Egyptian film industry and Egypt became the largest exporter of film and musical content to the Arab world. In 1933, “The White Rose” directed by Muhammad Karim became the first Egyptian musical. It starred the legendary Arab singer, Abdel Wahab. The popularity of the music helped “The White Rose” to become an instant hit and was shown in Arab countries around the world.

Now considered icons of Arab music, singers Um Kulthum, Farid el Atrash, Abdel Hatem and others grew famous through their appearances in these musical films. During WWII, Hollywood productions slumped and it was more difficult to obtain the popular films from Europe and America. As a result, the Egyptian industry boomed, filling the gap by producing films that mimic the European and American cinematic styles.

In Egypt, cinemas were set up in what you could call a pyramid structure: divided into three classes of society. There were first class cinemas, for the wealthy and refined; second class; and third class, which became known as “Cinema Terso.” The third class cinemas created a genre of their own and these B-films grew in popularity due to actors such as Farid Shawk, known as the “King of Terso.” According to Culture Trip, Farid Shawk’s films “represented the masses’ dream of defeating the wealthy.”

By 1952, the start of the Nasser era, the Egyptian film industry was producing an average of fifty films a year. Nasser nationalized the film industry (as he did with many industries in Egypt) and saw cinema, like many of his authoritarian-leaning counterparts around the world, as a tool to manipulate your message. So for a while, at least, cinema flourished under Nasser, but eventually the censors got tighter and tighter and as other world affairs began to take priority, the cinema industry eventually slumped.

Films that were acceptable during Nasser’s years were ones that criticized the former leaders. The same type of films that were banned under the monarchy for such behavior. I see it as no different than one Pharaoh scratching out the cartouches and faces of his predecessors.

The 1957 film, “Rodda Qalbi” (“Back Alive”) was made as a tribute to the 1952 revolution and apparently is still shown on TV every year on the anniversary of the coup, July 23, Egypt’s National Day.

In 1969, Shadi Abdel Salam wrote and directed “Al Mummia,” known in English as “The Night Of Counting The Years,” which the World Cinema Foundation restored in 2009.

When I first watched “Al Mummia,” I confess, I found it to be unbearably slow. But the more I toured Egypt and flitted between Ancient Egypt and modern times, the more I came to appreciate this film.

The tone is mystical, teetering on horror. It has intriguing imagery, locations, and people. Its saturated colors play with stark contrasts between blacks and whites. On one side you have a tribe of mountain men dressed in black hooded robes; on the other, elite individuals from the city: high officials and academics dressed in slick white clothes.

In the movie, loosely based on a true story, the mountain men are part of a fictional tribe; keepers of a secret: Hidden tombs which they live on top of and rob treasures from. The tribe’s chief dies, the son takes over… but the son is hesitant to keep stealing the treasures. He eventually comes to work with the city officials who are searching for the lost tombs of the pharaohs’ 11th dynasty, to preserve the heritage and put it in a museum.

Throughout my time in Egypt, I realized that “Al Mummia” touches upon so many themes that still plague Egypt today. The film deals with black market sales of antiquities, tribal allegiances and the question of who has ownership over Ancient Egypt. The locals protecting it, or the scholars preserving it?

One of my favorite movies from modern Egypt is Yacoubian Building, a 2006 film based on a novel of the same name, directed by Marwan Hamad with an ensemble cast that weaves multiple storylines of individuals trying to survive in modern day Cairo. It shows both the good and the bad of Egypt, and tackles some sensitive topics, from extremist religion to homosexuality to poverty and corruption.

Some of Egypt’s most successful mainstream movies, “The Blue Elephant” 1 and 2, were also directed by Marwan Hamad. Released in 2014 and 2019. The sequel broke box office records as the highest grossing film in Egypt’s history. The production of “The Blue Elephant” rivals the best of Hollywood and is celebrated in Egypt for its visual effects.

Filmmaking evolved as a result of the 2011 Arab Spring. On February 11, 2011 longtime ruler, Hosni Murabak resigned the presidency as a result of the Tahrir Square protests, ignited by the Arab Spring.

Egyptians from all walks of life gathered. Many were fighting against the widespread corruption of Murabak’s regime and police brutality; and fighting for freedom of speech and civil liberties. People protested because of high unemployment, low wages, and inflation on food prices.

Many filmmakers participated in the Arab Spring, and as this was the early stages of smartphones and social media, the people found a new way to share their voices and to be heard.

Every day citizens started filming evidence of police brutality on their cell phones and DSLR cameras. Protestors were being taken into the Egyptian Museum directly across from the park and being tortured, beaten and even killed by police. And it is because of citizens and press who staked out in nearby hotels and apartments, who were able to film and stream these instances live, that Mubarak’s regime was forced to face the consequences. It changed both the act of filmmaking and social activism.

The 2012 Oscar nominated documentary “The Square” delves into the on-the-ground realities of the Arab Spring revolution.

Some Websites that discuss Egyptian Cinema:

https://researchguides.dartmouth.edu/nationalcinemas/egypt

https://guides.library.cornell.edu/MidEastCinema/Egypt

https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/2011/introduction-to-egyptian-cinema/

https://goldenglobes.com/articles/century-egyptian-cinema/

https://www.meer.com/en/73865-the-influence-of-egyptian-cinema-in-the-arab-world

https://www.cnn.com/2016/12/06/middleeast/egypt-revolution-cinema

https://www.screenglobalproduction.com/country/egypt/guide/production-guide

Suggested Films From Egypt:

“The Blazing Sun” (1954) directed by Youssef Chahine

“Cairo Station” (1958) directed by Youssef Chahine

“Saladin the Victorious” (1963) directed by Youssef Chahine

“The Night Of Counting The Years” aka “Al Mummia” (1969) directed by Shadi Abdel Salam

“The Yacoubian Building” (2006) directed by Marwan Hamed

“In Search Of Oil And Sand” ( 2012) directed by Wael Omar and Philippe Dib

“The Square” (2013) directed by Jehane Noujaim

“The Blue Elephant” (2014) directed by Marwan Hamed

Cinema Landmarks To Visit:

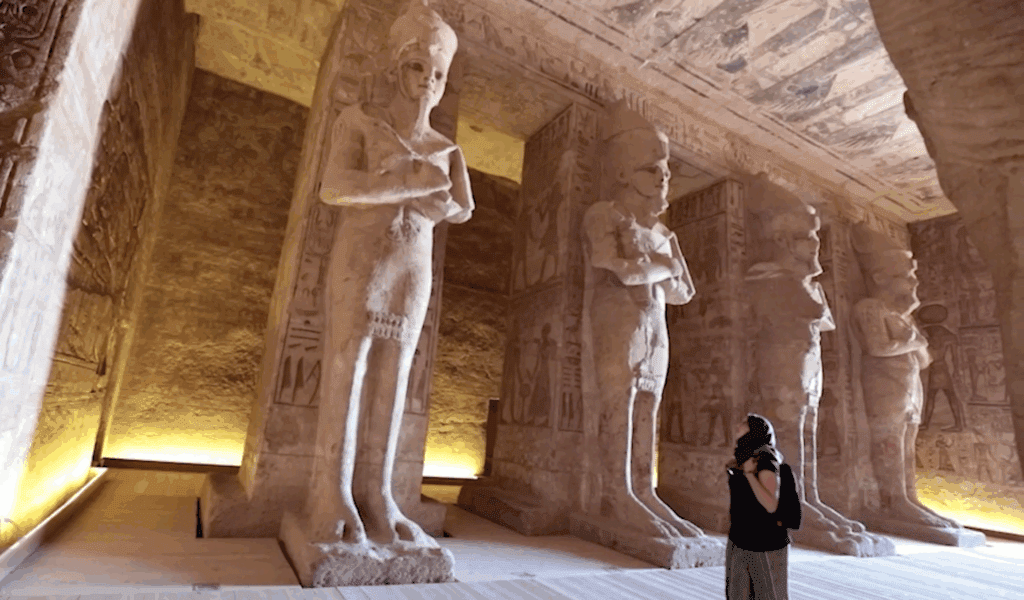

Karnak Temple in Luxor has appeared in films, including “The Blazing Sun” (1954) directed by Youssef Chahine, “Death On The Nile” (1978) directed by John Guillermin, and “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977) directed by Lewis Gilbert

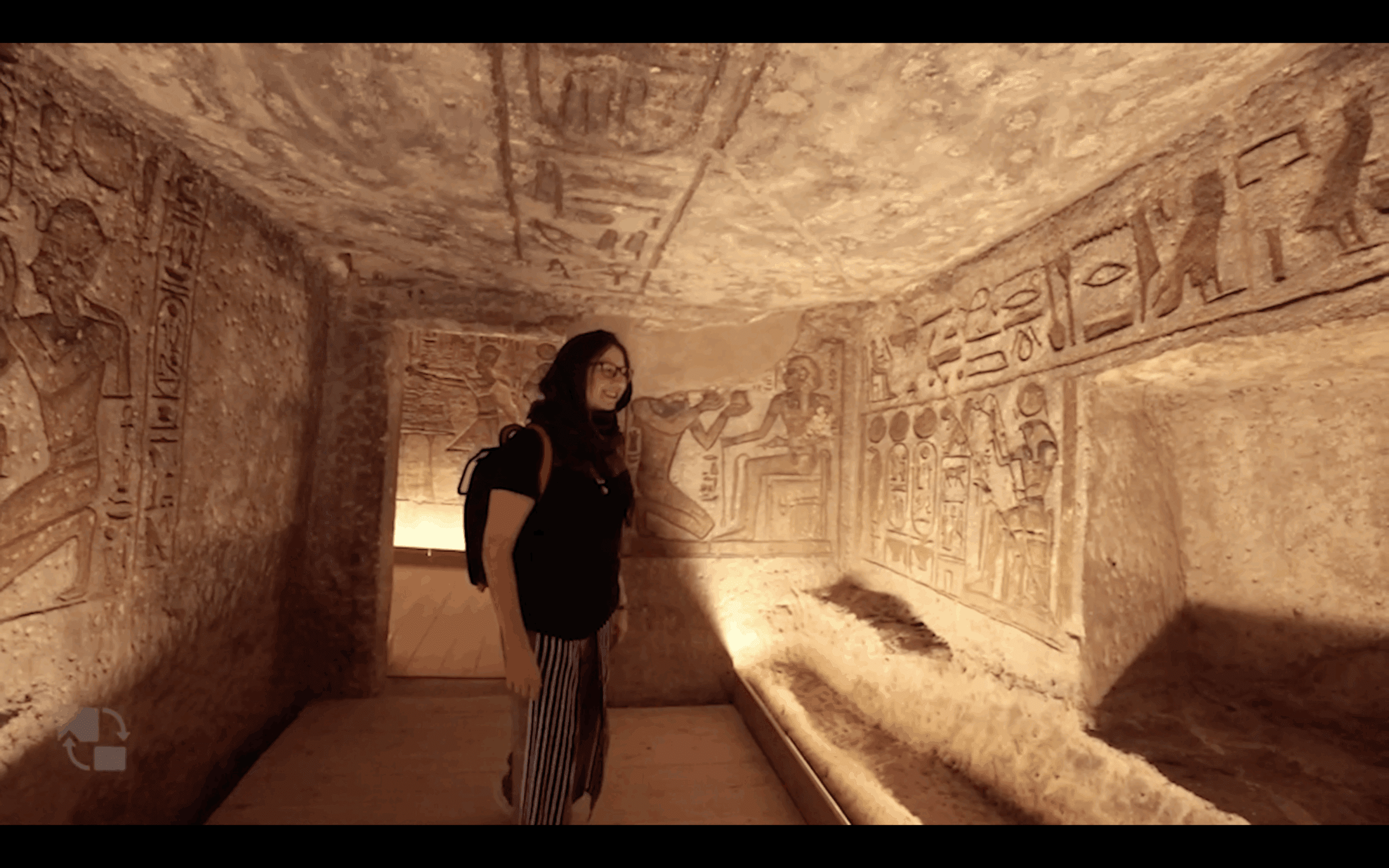

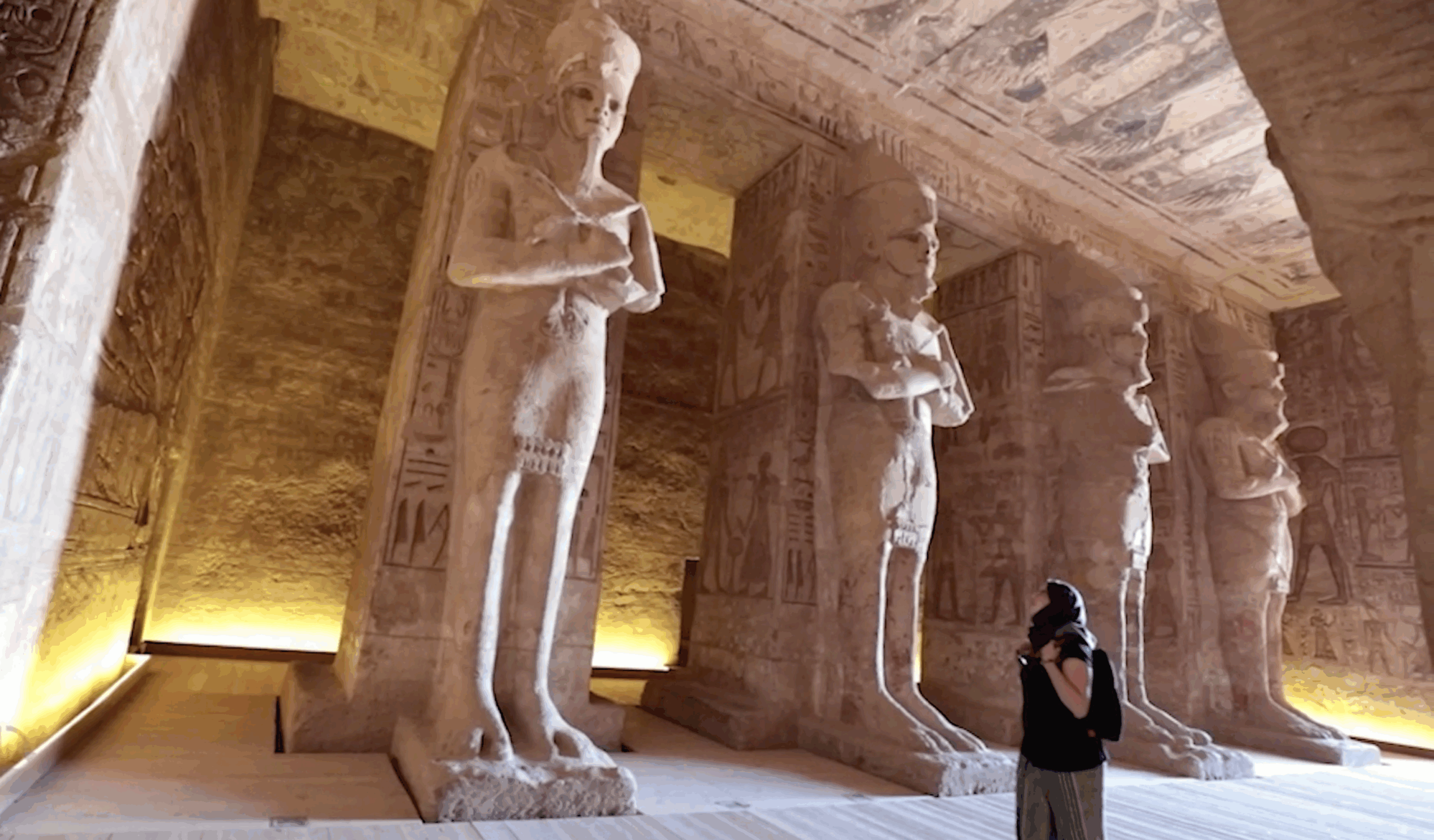

The Temple of Abu Simbel south of Aswan has appeared in films such as “Death on The Nile” (1978) directed by John Guillermin and “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977) directed by Lewis Gilbert; and “Valley of the Kings” (1954) directed by Robert Pirosh, filmed all over Egypt

The Great Pyramids of Giza have been featured in many movies as well, including Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009)

Cairo has served as a filming locations for many films, including, Spike Lee’s biopic, “Malcolm X” (1992), including at the The Muhammad Ali Mosque; and “Fair Game” (2010) directed by Doug Liman“A Hologram For A King” (2014) directed by Tom Tykwer and starring Tom Hanks, set in Saudi Arabia, was filmed in the Red Sea resort city of Hurghada

Official Name: Arab Republic of Egypt

Population: ~115 million

Capital City: Cairo

Form of Government: Republic

Official Language: Arabic

Currency: Egyptian pound

Borders: Libya, Sudan, Israel and Palestine, Mediterranean Sea, and Red Sea

About Egypt

Egypt, “the Mother of the World” as it is lovingly called, has a population of over 100 million, and a recorded history dating back over 7,000 years.

In ancient times, its civilizations thrived thanks to the agriculturally-fertile Nile River, and the river still holds an important place in Egyptian society today.

Historically, Egypt is split into Upper and Lower. Upper Egypt, represented by the lotus flower, consists of the southern kingdoms of the Aswan and the Nubia. Lower Egypt, the papyrus, is that of the northern and Delta region, where Cairo and Alexandria lie.

Ancient Egypt had at least 32 known dynasties. Sometimes the society crashed and had to be rebuilt again, sometimes it was occupied by foreign leaders and it passed through the hands of the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, who were conquered by the Byzantines and eventually the Arabs who brought in Islam; to the Mamluks, and the Ottomans, with a brief appearance by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon invaded Egypt and defeated the Mamluks at the Battle of the Pyramids in 1798. Though he only ruled for a whopping three years, he revamped taxes; brought in the metric system; the first printing press to Africa; and 167 scholars and artists, whom he commissioned to make a complete study of Egypt’s monuments, arts, crafts, flora and fauna. Napoleon’s impact on Egypt, especially bringing in the field of Egyptology, is still undeniably strong.

Most scholars consider the start of modern Egypt as the rise of Muhammad Ali, the Albanian prince. Ali modernized Egypt’s army, built a navy, roads, canals, initiated public education, improved irrigation and planted cotton, which is still one of Egypt’s largest exports.

After Muhammed Ali, his heirs took over and continued to industrialize Egypt.

In 1869, the Suez Canal opened, which became a major trade route and was coveted by France and Britain, eventually leading to Britain’s takeover. In 1882, the era of the “veiled protectorate” began, with Muhammed Ali’s heirs remaining on the throne under British influence.

In 1919, Britain granted Egypt its sovereignty, while still keeping a tight control over her rulers. King Fuad was followed by King Farouk, until he was ousted in a military coup in 1952, led by Colonel Nasser and “the free officers” corps. President Nasser became the first Egyptian to rule Egypt since the time of the Pharaohs.

Nasser led through a Marxist-Lenninist ideology, and during this time cinema flourished: the industry produced fifty films a year!

The country’s landowners were disposed, and assets nationalized. Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and built the Aswan High Dam to control irrigation and create hydropower.

The film industry was nationalized, too. Foreigners were kicked out, and Egyptians continued the trend of making movies.

Eventually the censors got tighter and tighter. Films that were considered acceptable during Nasser’s years were often ones that criticized Egypt’s former leaders: the same type of films that were previously banned under the monarchy. I see this as no different than one Pharaoh scratching out the cartouches and faces of his predecessors.

After President Nassar died in 1970, Anwar Sadat took over and reversed most of Nassar’s policies. Sadat favored the U.S. and capitalism over the Soviets and communism.

In 1977, Sadat negotiated a peace deal with the Israelis, known as the Camp David Accords, where Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai in return for Egypt acknowledging Israel’s right to exist. As a result, Sadat was assassinated on October 6, 1981.

Vice President Hosni Murabak succeeded Sadat and ruled for the next 30 years.

On February 11, 2011 Murabak resigned the presidency as a result of the Tahrir Square protests, ignited by the Arab Spring.

Egyptians from all walks of life gathered. Many were fighting against the widespread corruption of Murabak’s regime and police brutality; and fighting for freedom of speech and civil liberties. People protested because of high unemployment, low wages, and inflation on food prices.

Many filmmakers participated in the Arab Spring, and as this was the early stages of smartphones and social media, the people found a new way to share their voices and to be heard.

Every day citizens started filming evidence of police brutality on their cell phones. Protestors were being taken into the Egyptian Museum directly across from the park and being tortured, beaten and even killed by police. And it is because of citizens and press who staked out in nearby hotels and apartments, who were able to film and stream these instances live, that Mubarak’s regime was forced to face the consequences. It changed both the act of filmmaking and social activism.

In 2012, in what is considered Egypt’s first true democratic election, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood was elected by popular vote. Morsi then granted himself unlimited powers, and pushed through a pro-Isalmist constitution.

He also, ironically enough (as Morsi was elected as a result of the revolution,) enacted laws to prevent public protests.

In 2013, there was another military coup, led by defense minister, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who passed laws to make it almost impossible to have popular uprisings against the government.

About Alexandria:

Alexandria, the second largest city in Egypt, is the stuff of legends.

With a population of over 5 million, Alexandria is a crucial port town situated on the Mediterranean Sea, named for its founder, Alexander the Great, who was welcomed as a liberator in 331 BCE after the Persians had been occupying Egypt.

Alexander trekked across the desert to Siwa Oasis to visit the Oracle of Amun, who decreed Alexander had divine rights to the throne of Egypt.

Good ole Alex did not stay much longer in Egypt, as he left for Mesopotamia and died less than 2 years after Alexandria’s founding.

Despite this, Alexandria became the cultural and scientific center of the Greek world, famed for its lighthouse and its library, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, which was infamously destroyed in a fire during the Roman period.

Scholars and philosophers such as Euclid, Archimedes, Plotinus, Ptolemy, and Aristophanes all studied in Alexandria, and locals are still proud of this tie to ancient history.

From its founding Alexandria was the capital of Egypt until the Arab conquest shifted the capital to Cairo in 972 CE.

About Cairo

Cairo is a city of approximately 22 million, and unlike many of the other places travelers visit in Egypt, not a pharaonic city. When the great pyramids were built, Cairo was not a city at all! Present-day Cairo was designed in 969 CE by the Fatimid Dynasty: much of Cairo was built from the stones taken from the pyramids in Giza.

In addition to mosque after mosque after mosque, and a few Coptic churches thrown in, we visited Saladin’s Citadel, used in Chahine’s 1963 epic period piece, “Saladin the Victorious,” Chahine’s first film in color.

About Luxor and Aswan

Situated on the Nile River, Luxor is in Upper Egypt (so Southern Egypt) and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It was the ancient city of Thebes, and now is like a giant open air museum with temples such as Karnak and the tombs found in the Valley of The Kings, Valley of the Queens, And Valley of the Workers, all worth traveler’s time and attention.

Approximately 150 miles south of Luxor lies Aswan, the southern frontier of Ancient Egypt, blending into the territory of the Nubian peoples. Aswan has 5 UNESCO sites, including “The Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbal to Philae.” Philae is an island temple dedicated to the cult of Isis.

The quarries near Aswan provided the granite used to build many of the ancient monuments. The Romans, Turks, and later the Brits used Aswan as a garrison. In modern times, Aswan is considered to be a winter-resort town. The city of Aswan is 7 miles North of the Aswan High Dam, built between 1960 and 1970.

Three Things To Do in Egypt

- With enough travel time, trek out to the Western Sahara and visit the Oasis towns, such as Siwa Oasis

- Visit the modern version of Alexandria’s Bibliotheca Alexandria

- Go to the Daraw Camel market on a market day

Stephanie’s Top 3 Travel Tips to Visit Egypt

- Limit the amount of equipment you bring into Egypt: security does not take kindly to cameras, even small ones; and try not to have too many hard drives on hand

- Know that you may be escorted by “tourist police”

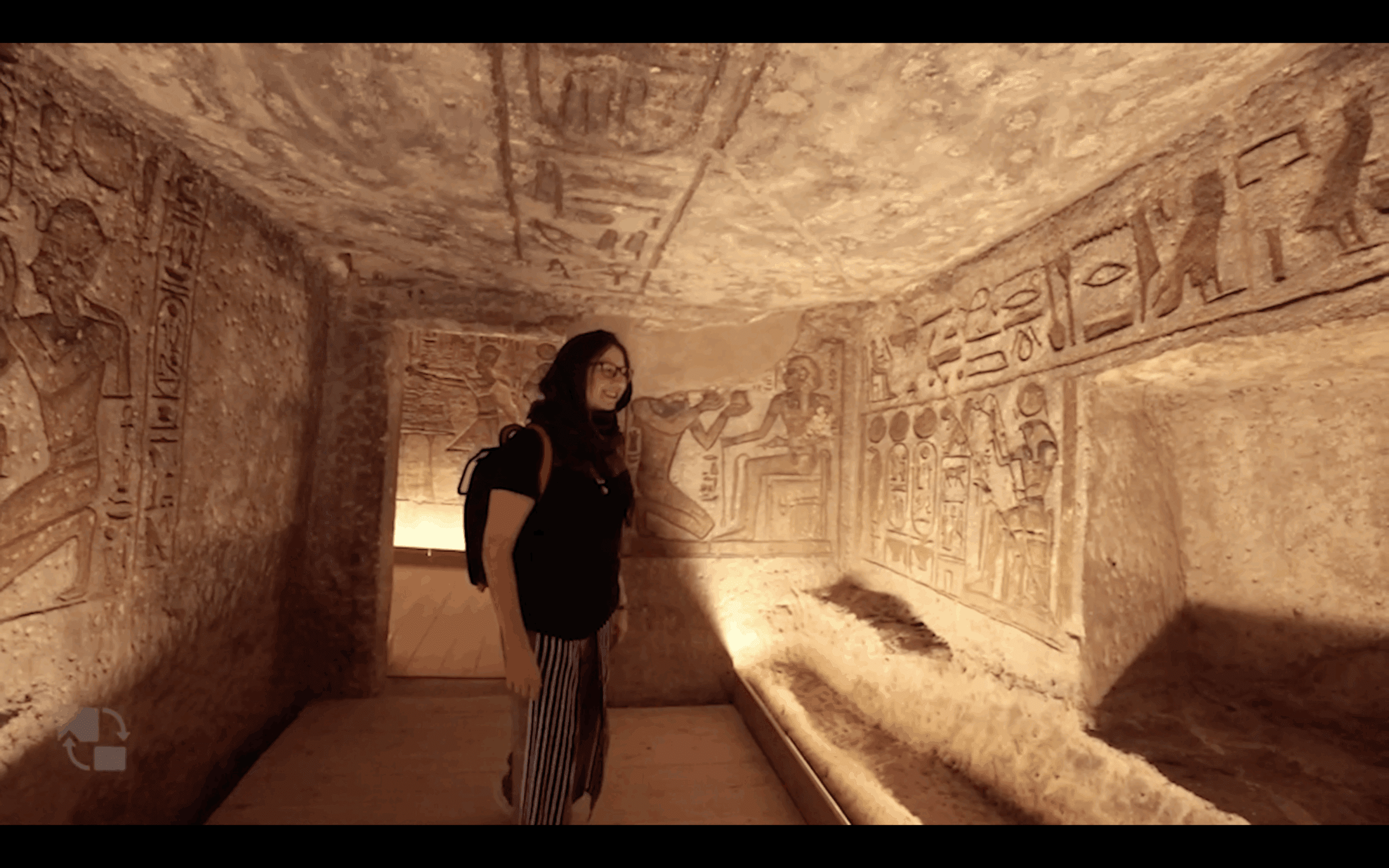

- Pay the extra fee to visit the Tomb of Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens. It may seem expensive, but if you have the money, it is worth it.

Useful Links:

- Mr History’s A Super Quick History Of Egypt

- Crash Course

- Lonely Planet

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/destinations/egypt

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/egypt-contemporary-culture

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/best-road-trips-in-egypt

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/things-to-know-before-traveling-to-egypt

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/what-to-eat-and-drink-in-egypt

- Britannica

- National Geographic

- Atlas Obscura

- CIA World Factbook

- BBC Country Profile

- WikiVoyage

Travel Blogs About Egypt