Brazil

106: Brazil

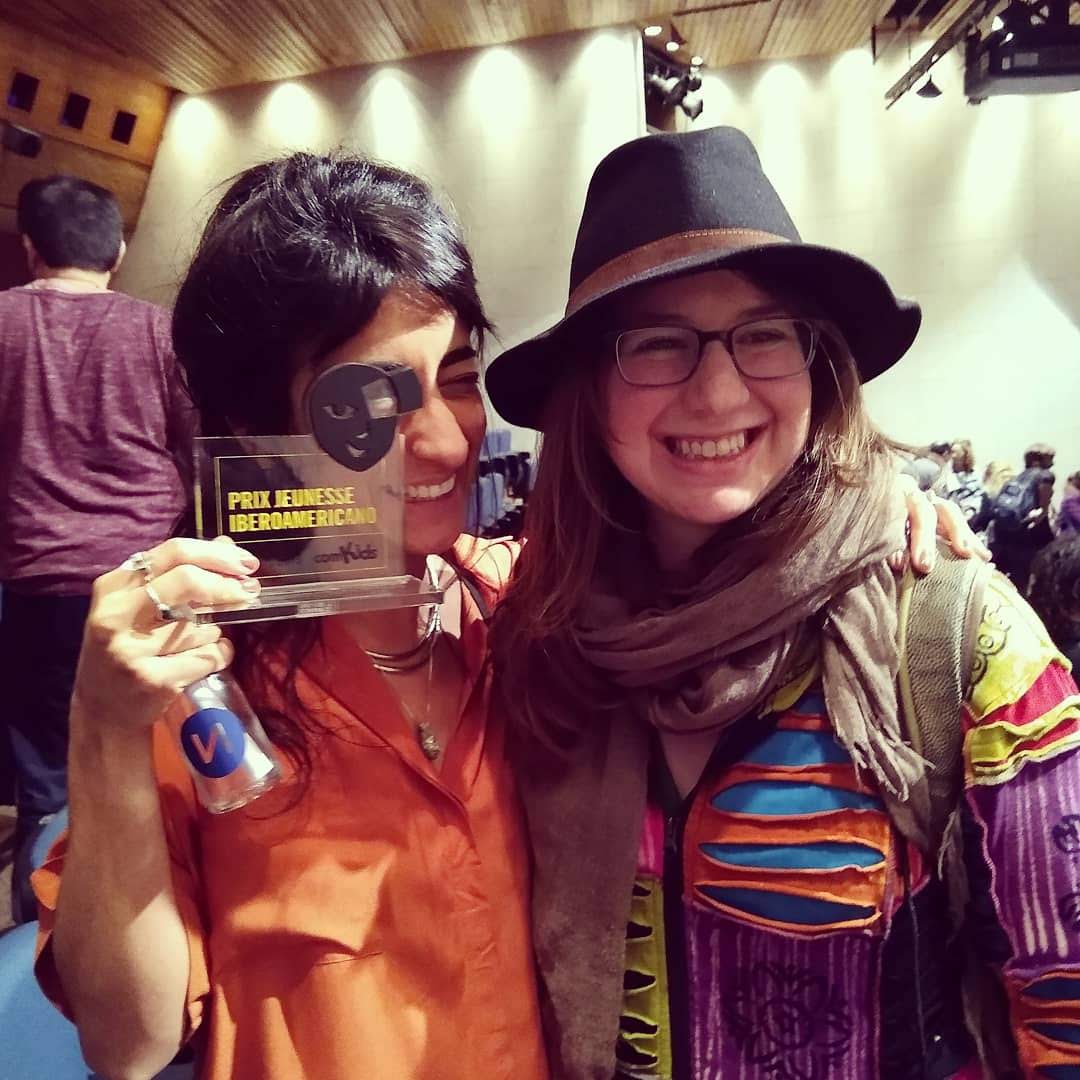

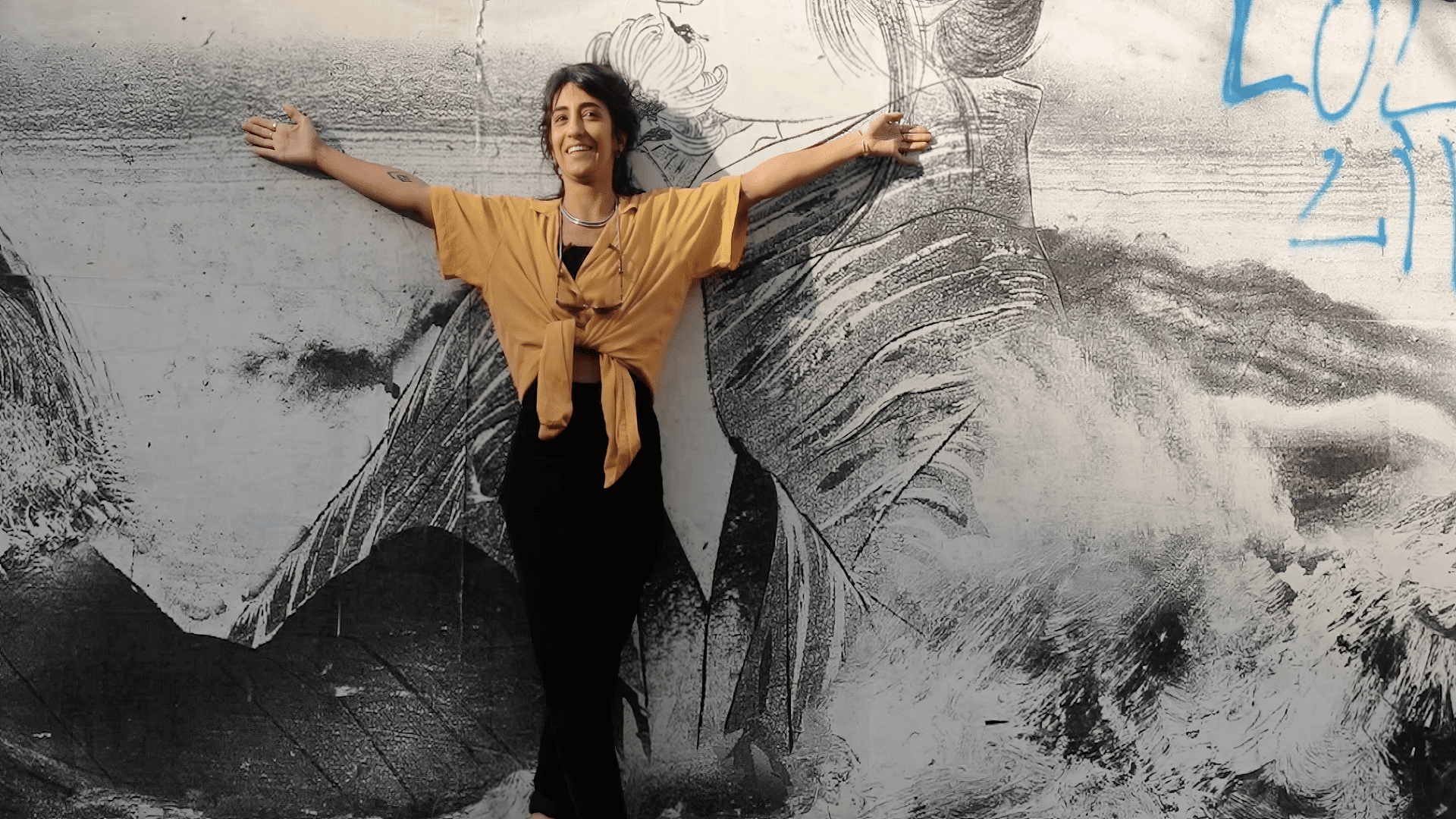

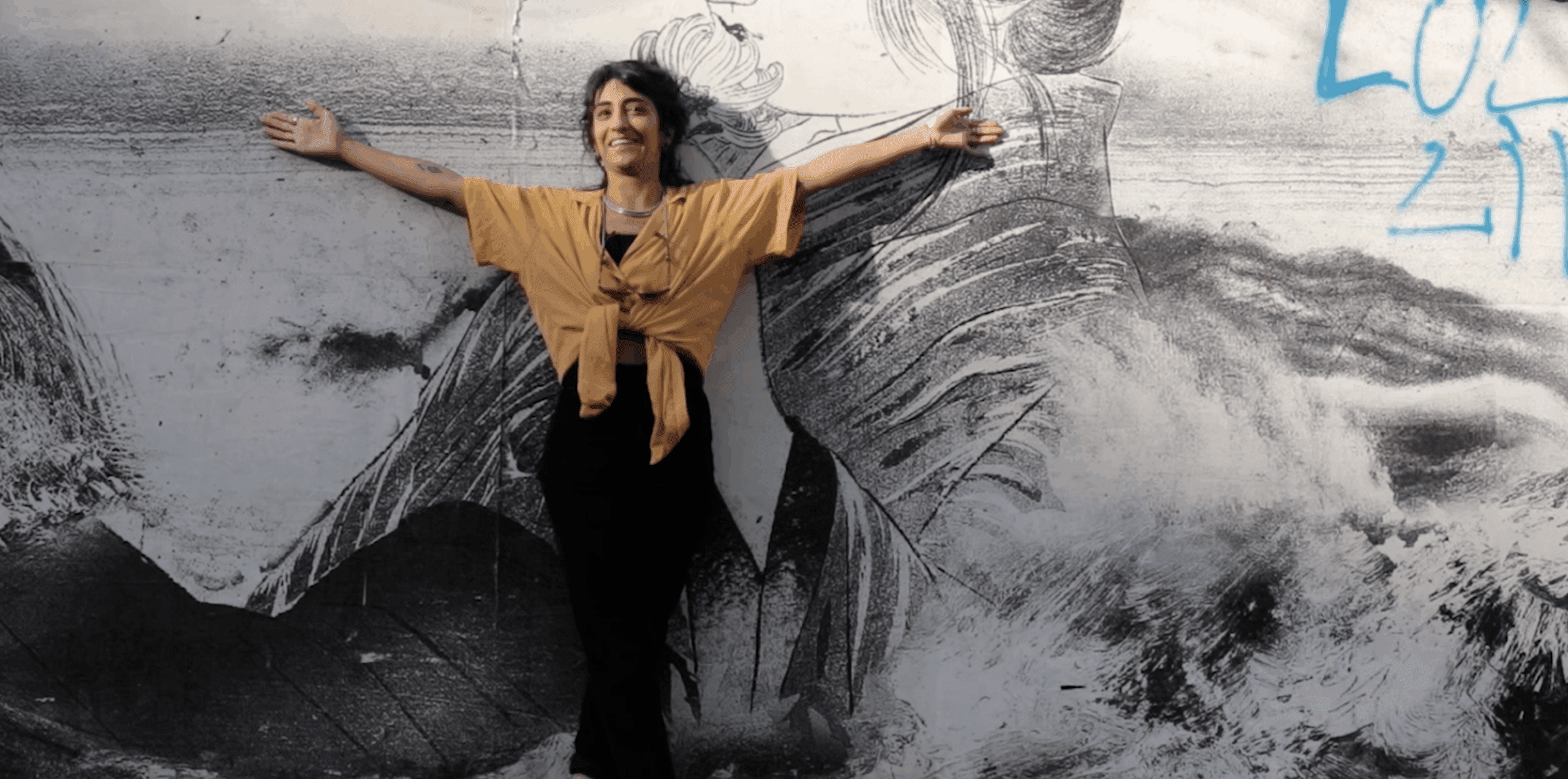

We travel to São Paulo to meet Paula, a dynamic woman who left a career as a professional journalist to become a documentary filmmaker, focused on stories that expose injustices and inequalities in Brazilian society. In São Paulo we scope out the street art splattered around the city; and our friend, Miro, takes us on a tour of Embu Das Artes, a community of craftsmen and artists.

Where Were You at 33?

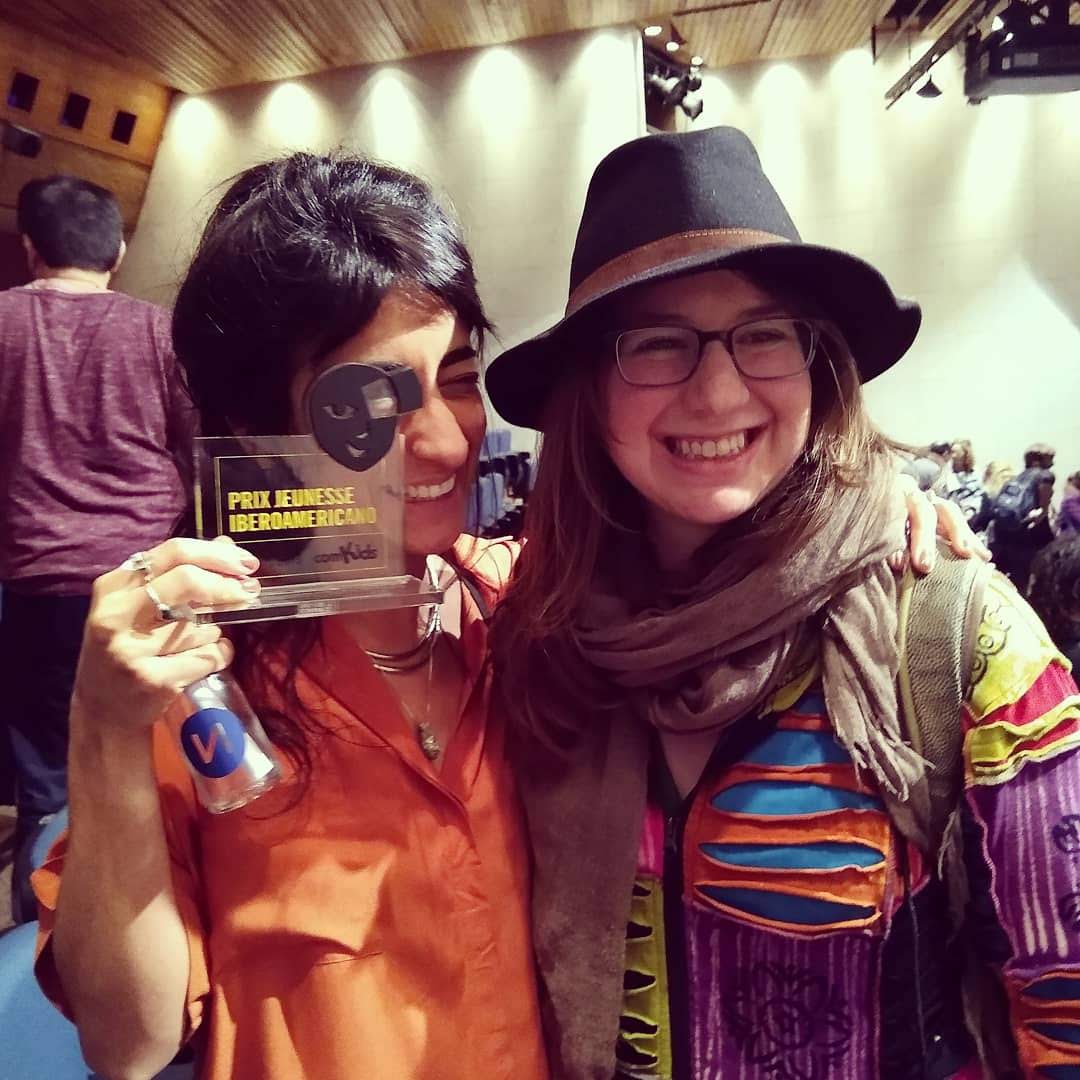

Name: Paula Sacchetta

Place: São Paulo, Brazil

Age at Filming: 31

Personal logline: “A girl who travels the world collecting stories so she can tell them.”

Directed by Paula:

“Verdade 12.528” (2012) co-directed with Peu Robles, “Faces of Harassment” (2016), “Famílias” (2019) TV series co-directed with André Bomfim, “Eu Preso” (2019) TV series, “Vozes do E!” (2021), “Turn On The Lights” (2021)

Watch: The Hardest Conversation To Have With Your Parents | NYT Opinion

Paula’s “desert island” films: “Nostalgia da Luz,” (2010) directed by Patricio Guzmán; “Grey Gardens,” (1975) directed by Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer; “La Lengua de las Mariposas” (1999) directed by José Luis Cuerda; “Los Silencios” (2018) directed by Beatriz Seigner; and “Lazaro Felice” (2018) directed by Alice Rohrwacher

Paula‘s Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/paulasacchetta

Paula’s Instagram: @paulasacchetta

More about Paula: https://www.wmm.com/filmmaker/Paula+Sacchetta/

https://videoconsortium.org/members/paula-sacchetta

Paula’s Bio: Paula is a journalist and documentary filmmaker. She won the Amnesty and Human Rights Vladimir Herzog Award for the magazine category. She covered the first Egyptian presidential elections in Cairo for Folha TV. She directed the documentary “Verdade 12.528” about the National Truth Commission. In 2014, her documentary short “Quanto mais presos, maior o lucro,” about the introduction of private penitentiaries in Brazil, was released, and she is the recipient of the 31st Human Rights and Journalism Awards. In 2016, Paula directed the transmedia project, “Faces of Harassment.” She directed the TV Series “Families” (co-directed by André Bomfim), produced by Brazilian Public Television.

Cinema of Brazil

The film industry of Brazil is one of the largest in Latin America (and possibly the world) and what’s most fascinating to me is the Brazilian knack for creating new genres.

Brazilians were quick to take a liking to filmmaking after the Lumiere brothers first released their innovative technology. The first public film screening in Brazil took place in Rio de Janeiro on July 8, 1896, after which film cameras soon arrived to Brazil.

On May 1, 1897, Vittorio di Maio’s “The Arrival of a Train in Petrópolis” was shown at the Cassino Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro, considered the first Brazilian film. Though many site Italian immigrant Alfonso Segreto’s 1898 film, “Vista da baia da Guanabara” filmed on a boat crossing from Italy, as the first Brazilian film. June 19th, the day that Segreto’s film was first screened in Rio, was declared as “Brazilian Cinema Day.”

In the early 1900s, Brazilians were making a unique genre of movies, called “posed films,” recollections of crimes that made the news, which became very popular. The first being, “Os Estranguladores” by Francisco Marzullo, released in 1906.

By 1908, Brazil was already entering a “Golden Age” of cinema with a plethora of silent short films being made. Especially popular were singing movies. Even though the films were silent, an actor stood behind the screen to sing along to the movie. Also popular were literary adaptations.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Brazil created Chanchada, which parodied the old Hollywood musical revue style mixing it with their own comedy and carnival-esque-ness. As a spin off, Brazil has a period of cinema that was almost entirely devoted to producing sex comedy films: Porno Chanchada, which spanned from the late 1960s into the early 1980s, its climax being in the late 1970s.

In more serious areas of the industry, the Cinema Novo movement during the late 1950s to early 1970s coincided with the French New Wave, but the New Wave films of Brazil tackled much heavier subjects than the romantics of France. A prelude to Cinema Novo is “Rio, 40 Degrees” (1955) directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, who went on to direct one of the highlights of Cinema Novo, “Barren Lives” (1963). Cinema Novo films represented a realism that the Chanchada films lacked, and tackled themes such as class struggles, and a so-called “aesthetic of hunger.” Filmmakers from this period include, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Carlos Diegues, Ruy Guerra, Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos.

The cinema of Brazil seems to be either a direct product of the government or a direct reaction to the political upheaval throughout Brazil’s rocky history of military dictatorships and multiple coups, which often resulted in censorship, even recently. For example, the Cinema Novo filmmakers were forced into exile in the 1970’s during the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas.

Brazilian films tended to be dark, thematically heavy, with periods of allegory, irony and parodies, often violent, and the comedies are extra dark. Like in Turkey and many of the other countries we later visited, the film industry of Brazil ebbed and flowed with the political strife of the country’s history, and in times of democracy, the output of productions significantly slumped.

The first internationally acclaimed film to come out of Brazil, is “Black Orpheus,” a 1959 French-co-production, controversial in Brazil for being directed by a foreign French man, Marcel Camus, while being touted as a “Brazilian film.”

By watching Marcel Camu’s 1959 film “Black Orpheus,” set in Rio de Janeiro during carnival, it’s easy to get swept up in the magic of the festivities and look past the true poverty of the favelas that the movie takes place in.

“Black Orpheus” elevates the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro to operatic status, as much of the film is sung rather than spoken, presenting us with a tragi-romance on the scale of Greek mythology. “Black Orpheus,” after all, borrows its plot from the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, previously adapted by the likes of Virgil and Ovid.

In the myth, Orpheus, the son of Apollo, falls in love with the beautiful Eurydice but their love is not meant to be. She dies on their wedding night and Orpheus manages to visit the underworld and convinces the gods to bring her back to life. The gods, moved by his love for Eurydice, grant him this wish on the condition that he does not look back at her until she is safely returned to the living. His love is so strong that he cannot resist looking back at her, and she is returned to the underworld for all eternity.

By watching Camu’s film, where a cacophony of characters are consistently smiling, you would think that everyone in Brazil perpetually sings, dances, plays music and fornicates.

The costumes and art design are colorful with the finest details; reds and golds dominate. It is a musical fantasy which introduced the world to Bossa Nova, and the score composed by Luiz Bonfá and Antônio Carlos Jobim is hypnotic. It is easy to fall in love with the cinematic and musical elements of “Black Orpheus.”

From the very opening scene, which follows a young boy playing on a hill as he flies a bright yellow kite high over the Rio de Janeiro valley, you cannot look away: it is a feast for the eyes and heaven on the ears. Kids play with goats and chickens in the backdrop, while Orpheus strums his guitar, sings a love ballad; a gentle melody that will be stuck in your head for days.

When “Black Orpheus” first came out, it mesmerized movie-goers around the world, earning a Palm d’or from Cannes and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, but looking back, the production of this film leaves a lot to reflect on.

Was it revolutionary for supporting an all black cast from Brazil? Or does the film objectify black men and women living in the favelas? Is it bringing awareness to the lifestyle and customs of Brazilians in Rio de Janeiro, or is the film simply “poverty porn?” Is it the first Brazilian film to make international waves, which paved the way for a strong cinema movement in Brazil, or is it wrong to even categorize this as a Brazilian film as it was directed by a French man with the backing of a French production company?

I am not here to answer these questions; it is not my place nor expertise. I can only encourage you to watch the film in hopes that it leads you down a similar rabbit hole of thoughtful exploration, as cinema so often provides us with more questions than answers.

A more recent and well known film from Brazil, is “City of God,” (2002) a heart-wrenching story and a brilliantly edited film, if you can handle two-hours of almost non-stop gunfire.

“City of God” takes place in the slums on the outskirts of Rio De Janeira and is about the life of hoodlums, who rob, steal, rape and murder to get what they want and survive amidst extreme poverty and violence. The film has a bit of a Tarantino edge to it and is broken into chapters, which are narrated by the film’s protagonist, a 16-year-old virgin adolescent (he is the last among his friends to lose his virginity), a thoughtful, observant, kind-hearted young man who’s one desire is to become a photographer. We see the world through his imaginary lens which ultimately becomes a real lens, when a photograph he took for the drug lord ends up on the front page of the Rio De Janeiro newspaper. “City of God” is based on a true story and gives viewers a glimpse of the favelas of Brazil that most people never see. This is a much harsher reality than that of “Black Orpheus,” set in the same region.

Other notable films include Hector Bebenco’s “Pixote” (1980), about a homeless adolescent boy who finds himself in juvenile prison and ends up wandering the streets of São Paulo, exploring its dark underworld; and Walter Salles’ “Central Station” (1998), which follows a nine-year-old boy who was sold into adoption to a crime ring who intends to harvest his organs. Salles later went on to win the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film for his film, “I’m Still Here” (2024), also nominated for Best Picture and Best Actress in a nod to Fernanda Torres’ performance.

There has been an emergence of a new generation of filmmakers in the twenty-teens creating a New Wave of Brazilian cinema that plays with “genre films” including, the horror-fantasy movie, “Good Manners” (2017) directed by Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra; ‘Bacurau,” a Western-sci-fi hybrid directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles; and the documentary “Let It Burn” directed by Maíra Bühler.

Some Websites that discuss Brazilian Cinema:

https://www.connectbrazil.com/brazils-cinema/

https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/things-you-should-know-aboutbrazilian-cinema

https://offscreen.com/view/intro_braziliancinema

https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/films-and-literature/films/

https://library.brown.edu/create/fivecenturiesofchange/chapters/chapter-8/cinema-novo/

https://thebrazilianways.com/history-of-brazilian-cinema/

https://www.travel-brazil-selection.com/informations/brazilian-culture/cinema/early-cinema/

https://www.marchedufilm.com/programs/brazil-country-of-honour/

https://variety.com/2024/film/global/globo-filmes-25th-anniversary-globo-brazil-1236005848/

Suggested Films From Brazil

“Limite” (1931) directed by Mário Peixoto

“Black Orpheus” (1959) directed by Marcel Camus

“Barren Lives” (1963) directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos

“Black God, White Devil” (1964) directed by Glauber Rocha

“Pixote” (1980) directed by Héctor Babenco

“Central Station” (1998) directed by Walter Salles

“Bicho de Sete Cabeças” (2000) directed by Laís Bodanzky

“City of God” (2002) directed by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund

“Bacurau” (2019) directed by Kleber Mendonça Filh and Juliano Dornelles

“I’m Still Here” (2024) directed by Walter Salles

Cinema Landmarks To Visit:

Teatro Amazonas in Manaus, Brazil

Museum of Image and Sound in São Paulo

Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB) in Rio de Janeiro

Official Name: Federal Republic of Brazil

Population: 212million

Capital City: Brasília

Form of Government: Democratic Federal Republic

Official Language: Portuguese

Currency: BrazilianReal

Borders: Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Atlantic Ocean

About Brazil

Brazil is one of the most populous countries in the world, with a population of over 212 million. It comprises one-third of Latin America’s population. Brazil is the largest nation in South America, taking over half the continent and bordering every South American country except for Chile and Ecuador. Home to a large swath of the Amazon, due to its vast size, Brazil has a large variety of flora and fauna and an eclectic mix of climates: from tropical climates in the north, to temperate climates in the south.

Brazil was home to a variety of indigenous populations prior to the arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral, a Portuguese explorer who arrived in 1500, and claimed the land for Portugal, which then took enslaved Africans to work on plantations. Sugarcane, diamonds, and gold were all exported back to Europe. Brazil remained a colony until 1815, when it became a kingdom within Portugal, but shortly thereafter in 1822, Brazil declared its independence. Brazil still had Portuguese kings, but by 1888, it became a Federal Republic after a military led coup’d’tat.

Brazil’s first constitution came in 1824, which granted freedom of religion and the press, yet maintained slavery. Brazil abolished slavery in 1888, the last country in the Western hemisphere to do so.

A 1930 armed conflict brought dictator Getúlio Vargas to power. He was named President and started out with democratic ideals, but after a self-coup in 1937, Vargas assumed even more powers, shut down the legislature, and invoked a new constitution with an increasing number of restrictions for his citizenry.

Democracy was briefly restored in 1945, only to be overtaken by another series of brutal dictatorships.

From 1964 – 1985, a conservative privileged class led an anti-communist military dictatorship, which is now most remembered for its human rights abuses, including, censorship, torture, disappearing people who disagreed with them, and extrajudicial killings.

1985 brought back a civilian government, and in 1988, Brazil’s current constitution was enacted.

In 2012, after nearly fifty years since the start of the military dictatorship, Brazil finally created a “National Truth Commission” to investigate the human rights violations of the authoritarian military dictatorship which ruled from 1964-1985, with horrors going even further back; a shockingly long timeframe which spans multiple generations. The commission had access to government documents from the previous years and on December 10, 2014 it issued a report, which released findings of over 337 government agents who were responsible for torture, inducing arbitrary prison sentences, forced disappearing of citizens, and deaths of political opponents. The reports found that over four hundred people were killed or went missing and at least 8,000 indigenous people were executed during the same time period, though scholars believe these numbers are much higher.

The modern politics of Brazil are much too complicated for me to dive into and so I highly recommend watching the 2019 Oscar winning documentary, “Edge of Democracy,” which outlines the rise and fall of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or “Lula” as he is known by his fans; Brazil’s former and now current president who was jailed for corruption, and many believe wrongfully so. It shows the rise and fall of Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s first woman president, who vowed to expose and put an end to corruption in Brazilian politics and as a result was impeached (to oversimplify it) for misuse of funds. It is believed by some that this was another plot from the opposing party to hide their own corruption and extortion of funds.

To put it into some perspective, Eduardo Cunha, who was the President of the Chamber of Deputies (part of their Congress) who led the impeachment charge, was previously investigated under Rousseff’s “Operation Car Wash” for allegedly receiving bribes and keeping secret Swiss bank accounts. Operation Car Wash started as a money laundering investigation and exposed major corruption at the highest level of government, from former presidents to governors to their chamber of deputies, senators and beyond. It was made internationally famous after it exposed the top officials at Petrobas, the state-run oil company, accusing them of accepting bribes in return for inflating construction contracts.

The movie also shows the rise of Jair Bolsonaro, from the opposition party, who has a more nationalistic approach to politics and ran for president to replace the impeached Dilma. He won after winning a campaign that he intentionally ran very similarly to Trump’s first campaign in 2016 in the United States.

In 2022, in a very tight race, the citizens of Brazil democratically elected Lula da Silva back into the office of the president, defeating the incumbent Bolsonaro.

About São Paulo

São Paulo, the city, with a population of around 12 million Paulistas (and approximately 22 million in the greater metropolitan area), is the largest city in Brazil, and also the capital of the state of São Paulo. It’s considered the industrial center of Latin America, and the state of São Paulo produces much of the coffee that comes from Brazil. São Paulo got its name from the Jesuit Missionaries who founded the city in 1554, in honor of the anniversary of the conversion of Saint Paul. Located in the Brazilian Highlands, the city is situated on the Tietê River. In the late 1800s, after slavery was dissolved, there was massive immigration to São Paulo, with an influx of people from all over Europe, and eventually across the decades, from all over the world, including the largest diaspora of Japanese outside of Japan.

After arriving in São Paulo, our first stop was the Avenue Paulista in the Jardins neighborhood, which comes alive every Sunday as the hip place to spend the end of the weekend. For a few hours each week, the streets are closed off to traffic and it’s a big pedestrian-only block party with live music and reverie.

Everyone was out: kids skateboarding, teenagers on scooters, cyclists, street vendors, a VolksWagen bus that sells craft beer out of it, food stands galore.

We absolutely loved the murals and street art we saw all across the city. Most notably, the Beco do Batman alley, which translates to “Batman Alley” for its images of the famed superhero.

Three alleys merge into one brightly painted open-air gallery of wonderful street art and fancy graffiti.

The tradition of street artists from all over the world visiting this corner of the Pinherois district near Vila Madalena began in the 1980s when the first DC Comics superhero, Batman, was drawn on the alley’s walls. Students of the fine-arts began adding to this canvas, and tradition continues today with new artists painting over the fading facades from decades ago.

One piece that particularly stands out in my memory is an image of Batman, in his black and blue suit, cape and mask being embraced by Pelé, the celebrated Brazilian football star. We only see Pelé’s back, with his jersey on; his hands are around Batman’s neck as if he’s about to kiss Batman. Batman’s gaze is not on Pelé, but rather the viewer. (If there was a camera lens taking a photo straight on of the scene, Batman would be looking dead at the camera rather than Pelé.) Batman remains stoic. The entire piece is incredibly life-like. You almost want to grab them both and say, “what is the meaning of all this?” “Where do we fit in this crazy, chaotic world?”

Another day, we visited the Museum of Images and Sound, which had an exhibit of cell phone photographs taken by every-day Paulistas. It shows you the power of a single lens; that anyone with a phone and a perspective of their own can create a viewpoint to share with the world.

We also visited an exhibit at the Pinacoteca Museum which delved into the horrors of Brazil’s former dictatorship, which tortured journalists and anyone the government deemed leftist. The exhibit discussed the individuals that went missing during those years. Paula’s first documentary film, “Verdade 12.528” is about this very topic.

Three Things To Do in São Paulo

- Visit Avenue Paulista on a Sunday evening

- Explore the street art of São Paulo and visit Beco do Batman

Take a day trip to Embu das Artes

Stephanie’s Top 3 Travel Tips to Visit Brazil

- Check for required vaccinations needed to enter Brazil

- Learn some basic Portuguese

- In the cities, use regular street smarts – be aware of pickpockets, don’t walk alone at night, etc.

Useful Links: