Bosnia & Herzegovina

114: Bosnia & Herzegovina

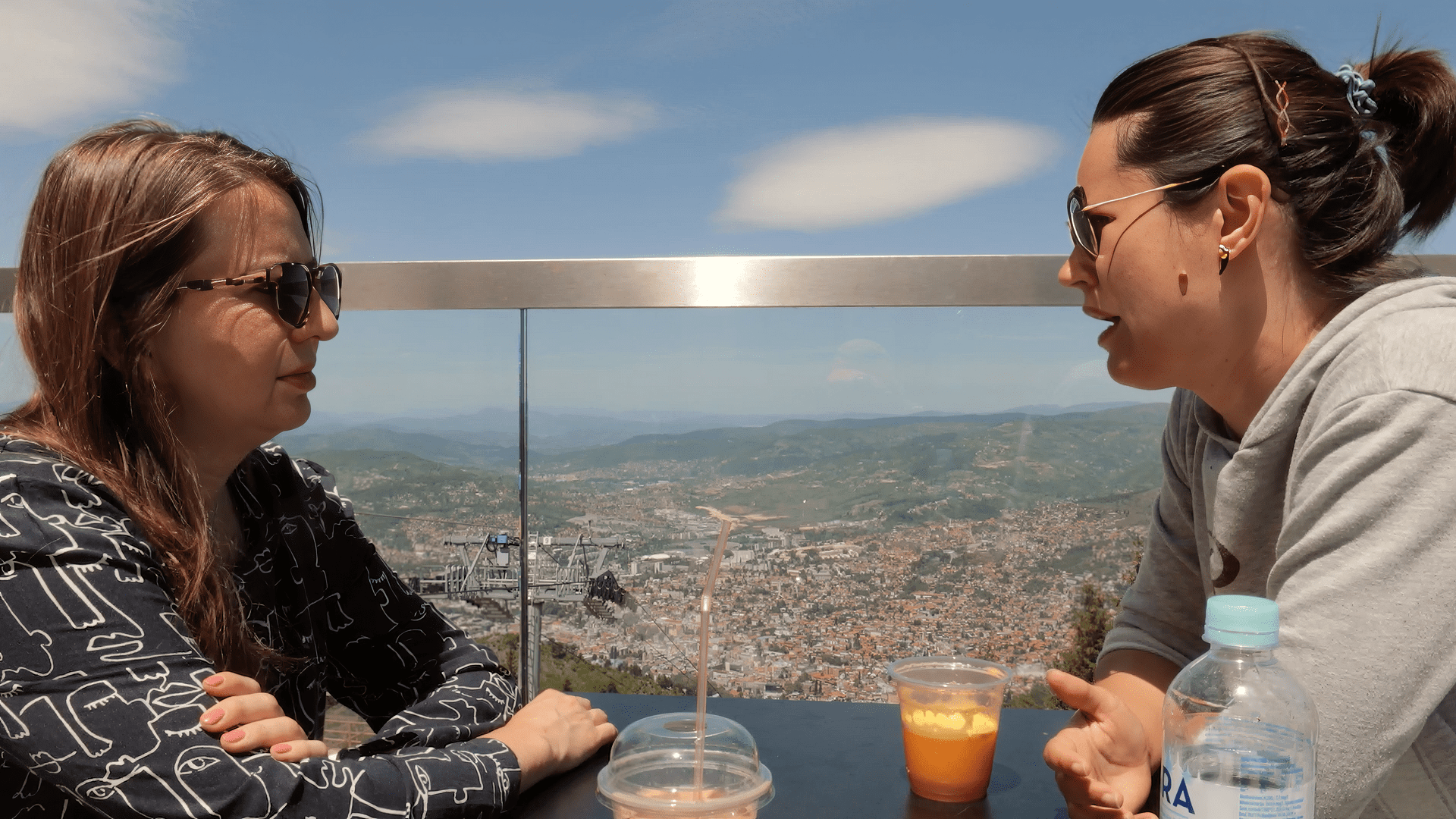

We explore Sarajevo, a city once celebrated as the “Jerusalem of Europe” for its multi-cultural diversity. Now full of survivors and poets, singers and creatives; stuck between the desire to break free from past terrors, along with the aim to “never-forget.” Writer, director, and academic, Tina, makes and studies films in order to process the horrors of the war she survived as a young child.

Where Were You at 33?

Name: Tina Šmalcelj (now Tina Kalinić)

Place: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Age at Filming: 33

Personal logline: A girl, who always knew how to find trouble, learns that she was actually looking for the tiny bits of luck scattered around the Universe.

Directed by Tina:

“Orfej” (2013), “Just Another Day” (2016), “Heart Of Stone” (2023)

Tina’s “Desert Island” films: “Hiroshima Mon Amour” (1959) directed by Alain Resnais, “Touki Bouki” (1973) directed by Djibril Diop Mambéty, “Rondo” aka “Roundabout” (1966) directed by Zvonimir Berković, “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” (2004) directed by Michel Gondry, and “The Intouchables” (2011) directed by Olivier Nakache and Éric Toledano

Tina’s Instagram: @tinasmalcelj

Tina’s Bio: Tina was born in Sarajevo in 1986. She has worked in film since 2007. In 2010, she attended Berlinale Script Station with her project “Summer Break.” Tina worked as the Sarajevo Film Festival’s Regional Forum Coordinator. She is an Assistant Professor on History and Analysis of Film at the Sarajevo Film Academy, and she is a Film New Europe correspondent for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Tina received an M.A. in Dramaturgy in 2014 at the Academy of Performing Arts in Sarajevo, and has a PhD in Filmology at the University of Zagreb. Tina works as a screenwriter and short film director. She is developing her first feature-length film to direct.

Cinema of Bosnia & Herzegovina

The cinema of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the cinema of Yugoslavia are inevitably intertwined.

Bosnia, as one of the six republics of the former Yugoslavia was a favorite destination for Yugoslavia’s prominent film industry. Yugoslav president Joseph Broz Tito was a huge cinephile, and it is said that he adored John Wayne and Hollywood westerns.

Tito had a heavy hand in the industry: he carefully reviewed screenplays, even giving feedback on the scripts, before green lighting the projects. The films of Yugoslavia were essential in helping to craft the narrative, and dare I say, “mythology” of the new Yugoslav identity — helping to create a Yugoslav historical narrative through entertaining storytelling.

The first feature to come out of Bosnia was the 1950 WWII partisan flick, “Major Bauk,” directed by Nikola Popović, a prominent Yugoslav actor and director born in 1907 in Gornji Milanovac, Serbia. “Major Bauk” is set in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s south-east region during World War II, when the Yugoslav Partisans were fighting against the Italian Fascists and Serbian Chetniks.

Several of Yugoslavia’s most famous Partisan war films were shot in Bosnia, utilizing their mountain scenery and their high-end production studio, BosnaFilm.

The must watch partisan films from Sarajevo-based-BosnaFilm include, “Battle of Susjeska” (1973) directed by Croatian filmmaker Stipe Delić, another WWII Partisan-victory film which stars Richard Burton as a young Joseph Broz Tito; “Walter Defends Sarajevo” (1972) directed by Hajrudin Krvavac, a filmmaker from Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; and the larger-than-life “Battle of Neretva” (1969) directed by Montenegrin filmmaker Veljko Bulajić.

My favorite movie of the era is the 1972 flick, “Walter Defends Sarajevo,” which stars famed Yugoslav actor Bata Živojinović, from Serbia. This movie seems to capture the heart and soul of Sarajevo.

“Walter” is the code-name for a real-life, much celebrated, WWII partisan resistance fighter, Vladimir Perić. Over time, “Walter” has become a symbol of Sarajevo, perhaps as a result of this film.

In “Walter Defends Sarajevo,” a Nazi captain is searching for “Walter” — the leader of the resistance. The German officer has been searching for over a year, yet has never found him despite deploying a “fake Walter” spy into the Partisan ranks. At the end of the film, the Nazi captain tells his superior, as he looks over a viewpoint of Sarajevo, “I finally know who Walter is.” He points to the city below. “This is Walter.”

“Battle of Neretva” was a Hollywood co-production which brought in Yul Brynner and Orson Welles and earned a 1970 Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, losing to “Z” from Algeria.

The story behind the filming of “Battle of Neretva” is almost stranger than fiction. Like “Susjeska,” the story of the film is Tito’s own as a World War Two partisan war hero, further helping to frame the origin story of Yugoslavia. In “Nerevta,” it is the story of the wounded. Tito himself was wounded in this battle and by making this film, Tito is reminding audiences he recovered to eventually save the day and free the people, creating a communist utopia.

In the Herzegovinian town of Jablanica is the actual Bridge on the Neretva, which was blown up not once, not twice, but three times! Once, intentionally, by the WWII Partisans, to serve as a decoy for the invading German army. After the Germans retreated, thinking the Partisans would no longer advance, the Yugoslavs rebuilt the same bridge and carried their wounded soldiers across to safety. This is the general plot of the movie version.

The second time the bridge was blown up happened during WWII in retaliation from the German army.

And the third explosion, infamously in Bosnia’s cinema history, was blowing up the bridge for the recreation in the film, to make this on-screen battle feel as authentic as possible.

Tito approved the explosion of the bridge, and even provided army tanks and explosives to aid the movie-production. It is said that actual Yugoslav army soldiers were acting as extras in the movie, playing the WWII soldiers on film.

Remarkably, Pablo Picasso created the film’s poster, only the second time he painted for film art, the first being for “Andalusian Dog,” and rumor has it, he did so only in exchange for a case of Yugoslavia’s best wine.

In the early 1980s emerged the filmmaking talents of Emir Kusturica, a controversial figure today. He was born in 1954 in Sarajevo to a “secular Muslim” family. He graduated from a prestigious film school in Prague, the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU), and his early films shot in Bosnia and Herzegovina are to some, considered his best works: “Do You Remember Dolly Bell?” (1981), a coming-of-age tale and “When Father Was Away On Business” (1985), and “Time of the Gypsies” (1989).

He is perhaps most famous for “Underground” (1995), a Felini-esque wartime dramedy set in Belgrade, which won him the Palm d’Or in 1995.

Today he considers himself Serbian, and has made his home in Küstendorf, also known as both Drvengrad and Mećavnik; a village in Western Serbia (near Mokra Gora) Kusturica constructed himself, originally as a film set to mimic a traditional village, which he used in his 2004 film “Life Is A Miracle.” The streets are named after famous film directors from around the world, there is a private cinema, a small chapel, and guests can come and stay overnight. There is an annual Film and Music Festival held here.

Kusturica has said in regards to this village:

“I lost my city [Sarajevo] during the war. That is why I wished to build my own village. It bears a German name: Küstendorf. I will organize seminars there, for people who want to learn how to make cinema, concerts, ceramics, painting. It is the place where I will live and where some people will be able to come from time to time. There will be of course some other inhabitants who will work. I dream of an open place with cultural diversity which sets up against globalization.”

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kusturica has another Disney-land-esq tourist village, Andrićgrad, which celebrates the Nobel Prize winning Yugoslav novelist, Ivo Andrić, most famous for his novel, The Bridge On The Drina.

This town is located in Višegrad, Republika Srpska region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where some of the worst atrocities of the Bosnian war took place.

During the wars of the 1990s, film production sunk to be nearly non-existent, however, the prestigious Sarajevo Film Festival sprung out of the war.

In the early-to-mid 1990s during the four-year-siege on Sarajevo, The Sarajevo Film Festival was formed “with the aim of helping to reconstruct civil society and retain the cosmopolitan spirit of the city.” (Festival’s website) and in the past 3 decades, it has grown to become the largest film festival in the region.

After the war, resurgence of filmmaking occurred in the early 2000s, thanks to a generation of filmmakers making war films, most notably, “No Man’s Land” (2001) written and directed by Danis Tanović and picking up an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. “No Man’s Land” was the first film from the former Yugoslavia countries to win an Oscar.

“No Man’s Land” takes place in 1993 during the Bosnia-Serbia war. A Bosnian and a Bosnian-Serb fighter find themselves trapped in the same trench with a third Bosnian soldier who is stuck dying on the top of a land mine set to explode.

What compels me about this film is that there are no false pretenses towards the situation: while there are a few brief moments of connection between these two opposing fighters, they certainly do not become friends, and their enemy status remains at large through the end.

Surprisingly, Tanović throws in a lot of humor throughout, most poignantly, through the use of language. The enemy-soldiers speak the same language, while the so-called peacekeepers do not —so the enemies end up translating for each other. It gives one pause to consider who’s fighting whom and why?

Other films to emerge in the 2000s include, “Fuse” (2003) directed by Pjer Žalica; “Go West” (2005) directed by Ahmed Imamović; “On The Path” (2010) directed by Jasmila Žbanić; “Cirkus Columbia” (2010) directed by Danis Tanović, and “The Bridges of Sarajevo” (2014) made by a coalition of thirteen directors, both Bosnian and foreign, such as Cristi Puiu of Romania and Jean-Luc Goadard of French-Swiss origin.

Notable directors include Danis Tanović (“No Mans Land,” “Cirkus Columbia,” “An Episode In The Life Of An Iron Picker,” “Not So Friendly Neighborhood Affair”); Aida Begić (“Snijeg,” “Djeca,” “Never Leave Me,” “Balada”) and Jasmila Žbanić (“Grbavica,” “Na Putu,” “Quo Vadis, Aida?”)

Almost every film I’ve seen from Bosnia is in one way, shape or form, a war film. From WWII to today. The exceptions are extremely rare. Surely, filmmakers are writing about what they know—and the prominent filmmakers to emerge in the 2000’s were from the generation who directly experienced war.

Part of this trend is also because filmmakers will not get funding, nor selected at prestigious international festivals, without themes that audiences, fests and funders expect from a filmmaker in Bosnia — and that is war.

The 2021 Oscars are proof of this as a Bosnian War film, “Quo Vadis, Aida?”, a harrowing depiction of the Srebrenica genocide, was one of five films nominated for Best International Feature Film. It lost to Denmark’s “Another Round.”

In the movie, Aida is an English teacher working as a translator for the UN, who hopelessly fights tooth and nail to try to save her husband and kids from the Bosnian-Serb forces who violently invade the designated UN Safe-Zone, to carry out the Srebrenicia massacres.

Anyone who remembers these events, knows that this story does not end well.

While “Quo Vadis, Aida” did quite well at the box offices in Bosnia, and screened to international acclaim, we came across a variety of strong opinions towards this film, ranging from those who absolutely despise it, to others who appreciated the realism of the film as a brutal moment in time that is necessary to remember.

Today, filmmakers Ines Tanović and Faruk Lončarevič, make films that deal with life of ordinary families in the aftermath of the war. Ines, director of the Film Center Sarajevo, wrote and directed “Our Everyday Life” (2015) and “The Son” (2019). Fauk, a professor at the Sarajevo Academy Of Performing Arts, wrote and directed “Mom and Pop” (2006) and “With Mom” and “So She Doesn’t Live” (2021).

The Film Center Sarajevo houses and preserves 80 feature films and over 500 docs and experimentals. The Free Cinema Walter screens these archival films to encourage young artists to know their cinema heritage and continue making movies.

Some Websites that discuss the Cinema of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Yugoslavia:

Film Center Sarajevo: https://fcs.ba/

Sarajevo Film Festival: https://www.sff.ba/en

Sarajevo City of Film: https://citiesoffilm.org/sarajevo/

Yugoslav Film Archives: https://en.kinoteka.org.rs/

https://fcs.ba/major-bauk-the-first-movie/

https://www.yugonostalgia.com/en/movies/the-battle-of-neretva/

https://sarajevotimes.com/know-story-battle-neretva/#google_vignette

https://researchguides.dartmouth.edu/nationalcinemas/yugoslavia

https://eefb.org/retrospectives/new-yugoslav-film/

https://www.tasteofcinema.com/2015/20-essential-films-for-an-introduction-to-yugoslavian-cinema/

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2022/after-yugoslavia/after-yugoslavia-an-introduction/

https://cinemawavesblog.com/movements-page2/yugoslav-black-wave/

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/black-wave-white-ray-yugoslav-film-1960s

https://balkandiskurs.com/en/2025/01/26/the-tale-of-the-bosnian-film-industry/

https://epicenter.wcfia.harvard.edu/podcast/ep16-rare-films-from-socialist-yugoslavia

Suggested Films From Bosnia and Herzegovina:

“Black Pearls” (1958) directed by Toma Janic

“Battle of Neretva” (1969) directed by Veljko Bulajić.

“The Role of My Family in the World Revolution” (1971) directed by Bato Čengić

“Walter Defends Sarajevo” (1972) directed by Hajrudin Krvavac

“Battle of Sutjesko” (1973) directed by Stipe Delić

“Landscape With A Woman” (1989) directed by Mirza Idrizović

“Do You Remember Dolly Bell?” (1981) directed by Emir Kusturica

“No Man’s Land” (2001) directed by Danis Tanović

“Grbavica” (2006) directed by Jasmila Žbanić

“Children of Sarajevo” aka “Djeca” (2012) directed by Aida Begić

“Snow” aka “Snijeg” (2008) directed by Aida Begić

“Quo Vadis, Aida?” (2020) directed by Jasmila Žbanić

“With Mom” (2013) directed by Faruk Lončarević

“Our Everyday Life” (2015) directed by Ines Tanović

“The Son” (2019) directed by Ines Tanović

“So She Doesn’t Live” (2021) directed by Faruk Lončarević

Cinema Landmarks To Visit:

Bosnia and Herzegovina Film Museum at the Film Center Sarajevo

Official Name: Bosnia and Herzegovina

Population: 3+ million

Capital City: Sarajevo

Form of Government: Tripartite Presidency

in a Parliamentary, Democratic Republic

Official Language: Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian

Currency: Bosnia-Herzegovina Convertible Mark

Borders: Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro and the Adriatic Sea

About Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Around 40% of Mountainous Bosnia and Herzegovina is covered in forests. With a population of 3.5 million it is bordered by Serbia, Montenegro, and Croatia: an almost landlocked country, which has a small strip of coast on the Adriatic Sea.

This former Yugoslav republic has 3 official languages and thanks to the 1999 Dayton Agreement, a Tripartite presidency: one Croatian, one Serbian, and one Bosnian-Muslim rotating positions every eight months.

The country is divided into two semi-autonomous entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic Srpksa, each with its own president and prime minister. With separate borders, different alphabets, flags and leaders, to me, these two entities feel very much like separate countries. Bosnia, and, Herzegovina are remnants of old kingdoms. (The larger northern territory is named for the Bosna River; the smaller southern section takes its name from the Old Serbian word herceg, meaning “duke,” combined with the possessive -ov and the suffix -ina, meaning “country,” to denote “dukedom” – from CIA Factbook)

Lonely Planet has described Bosnia and Herzegovina as: “East-meets-West atmosphere born of blended Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian histories filtered through a Southern Slavic lens.”

It can be controversial still to recall the History of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as different groups have different versions. Here’s a brief bullet-point synopsis leading up to WWI, gathered mostly from Lonely Planet books:

- 9 CE: Illyrian Bosnia conquered by Romans

- Slavs arrived late 6th century and were dominant by 1180 when Bosnia first emerged as independent under Byzantine ruler Ban Kulin

- “Patchy Golden Age” between 1180-1463 (peaking in late 1370s when King Tvrtko gained Hum (future Herzegovina) and controlled Dalmatia

- Medieval Bosnia had its own independent church (as Bosnia blurs the borderline between Catholic west and Orthodox east)

- By the 1460s most of Bosnia was under Ottoman control. “Easy-going Sufi-inspired islam became dominant” (Lonely Planet) Ottoman era produced infrastructure, including mosques and bridges, but by the late 19th century, it had incurred high debt and high taxes

- In 1874 BiH’s harvests failed, so paying taxes would mean starving. *With nothing left to lose, the mostly Christian Bosnian peasants revolted, leading eventually to a messy tangle of pan-Balkan wars.” (Lonely Planet)

- Pan Balkan wars ended with 1878 Congress of Berlin — Western powers carved up Ottoman land and “Austria-Hungary was ‘invited’ to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina; they were treated like a colony, while also providing much development of roads, railways, bridges; the coal mining and forestry industries boomed

- New Nationalist sentiments were brewing: “Bosnian Catholics increasingly identified with Croatia, while Orthodox Bosnians leaned towards ‘Serbia’s dreams of a greater Serbian homeland!’

- In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there was an approximately 40% Muslim population, who started to form their own cultural group

- After 1908, the Young Turk revolution kicked off the Balkan Wars of 1912 & 1913

- On June 28, 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated (by Serbian Nationalists in Sarajevo) and a month later, Austria declared war on Serbia, jump starting World War I.

In 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian empire fell, the first Kingdom of Yugoslavia was formed, known as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

During WWII, Yugoslavia was forcibly occupied by Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy.

Two distinct resistance movements sprung up: the Četniks, seeking a return to Serbian-led monarchy; and the Partisans, fighting for an anti-facist, pro-communist Yugoslavia. Leading the Partisans was Joseph Broz, known as “Tito.” The Partisans were victorious and a new Yugoslavia was formed with Tito serving as President For Life.

Yugoslavia consisted of 6 republics: Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Macedonia; each one had their own parliament and president. The motto became “Brotherhood and Unity.”

Yugoslavia’s communism was unique in the world. It was considered freer, and not associated with the Soviet Union. Tito masterfully played both the Eastern and Western powers to his advantage. And Yugoslavia became a prosperous nation.

After Tito’s death, the union started to crumble into a prolonged, painful breakup, and by the late ‘80s, the stage was set for the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. After Slovenia successfully succeeded relatively peacefully, an onslaught of conflict and wars continued through 1995.

For a more comprehensive yet digestible history of the former Yugoslavia and its wars, see this article from Rick Steves:

https://www.ricksteves.com/watch-read-listen/read/understanding-yugoslavia

About Sarajevo:

With a population of around 350,000, Sarajevo is the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city is situated on the Miljacka River, surrounded by the Dinaric Alps.

Sarajevo was long considered the “Jerusalem of Europe” for its multi-cultural population living side by side. Some of this may be overly nostalgic readings of history, I’m not sure, as today’s Sarajevo is divided by not-so-invisible lines – East and West – and with those who identify more as Serbian, or Bosnian, or Croatian.

People still talk of the “before” — meaning before 1992 when the Bosnian war took root, or before 1984, Sarajevo’s Olympic-last hoorah, or before 1980 when Tito died. Perhaps even before WWII, or before the Ottomans occupied the city in the 1400s. Sarajevo has been through a lot. And many inhabitants long for “the before.”

One thing is for sure, before the world wars, Sarajevo had one of the largest Jewish populations in Europe because people felt safe here. In WWIII, 84% of Sarajevo’s Jewish population was murdered. Sarajevo is a spirited city; it is a city with a soul, and many Sarajevans we met along the way spoke of their love for Sarajevo because of its multi-cultural background, and its creative spirit.

The height of Sarajevo’s glory was the 1984 Olympics, which is talked about and remembered with much nostalgia. You can still buy the souvenir mascot, Vusko, a grinning wolf who inspired me to visit the Olympic Museum in Sarajevo.

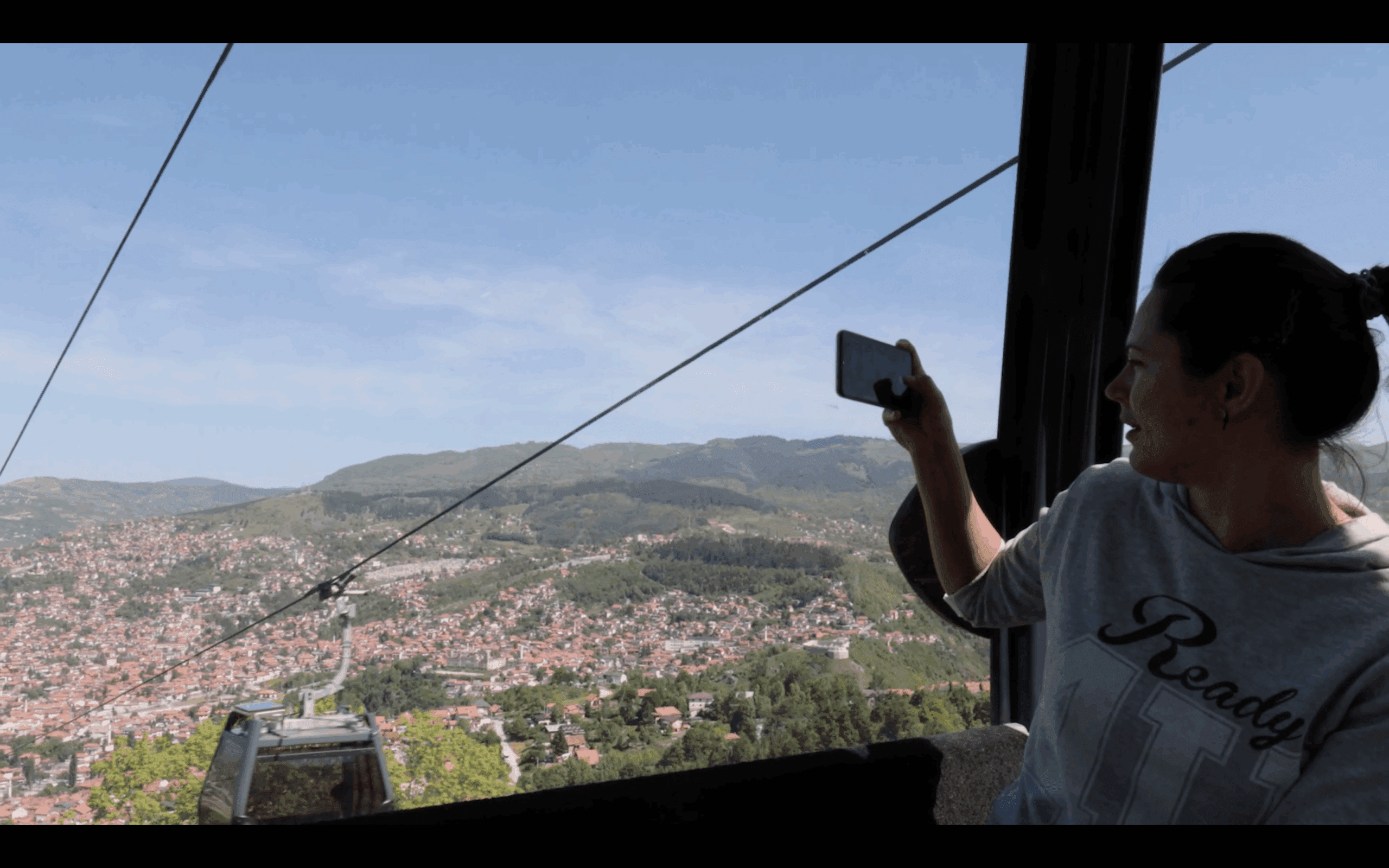

Tina and I took the Trebenic cable car up to the abandoned Olympic bobsled track to walk around its urban-park-like setting. Now used as a canvas for graffiti tags, this bobsled track is where, less than a decade after the Olympics, the Bosnian Serb forces were based during their nearly four-year siege on the city. Up to 14,000 people were reported dead during the siege (not including many, many more wounded) and a large percentage of the population lost their homes to sheer destruction.

Coming into Sarajevo, a quote Tina had written to me stuck in my head: She said, “Sarajevo is such a beautiful little city and it suffered a lot and I feel a great responsibility to give credit to the city that made me who I am every time I do anything creative.”

I had never before considered having responsibility to a place.

I was intrigued by this concept, and her words spiraled through my thoughts as I walked down the river, over bridge after bridge, past the corner where Franz Ferdinand jump-started “The Great War,” scooted my way through the labyrinth of old town, passing mosques, churches, and synagogues, libraries, battered and rebuilt, reminders of the past with glimmers of hope peaking through the spirited crowds people going about their daily business.

Less than a decade after the celebrated Winter Olympics, from 1992 to 1995, Bosnian-Serb forces seeking to take control of the land, surrounded the city of Sarajevo and maintained a nearly four-year siege on the city. Sarajevo was pounded by Bosnian-Serb shelling from the surrounding mountains; it’s only access to the outside world was via a secret tunnel under the airport runway. This shelling and additional sniper fire, often taking place down the infamous “Sniper Alley” along Sarajevo’s main avenue, killed at least 10,500 Sarajevans and wounded at least 50,000 more.

In 2019, Sarajevo was named a UNESCO City Of Film.

More about the City Of Film: https://citiesoffilm.org/sarajevo/

About Srebrenica:

I decided to take a trip to the salt-mining town of Srebrenica, now a part of the Republic of Sprska, to visit the Srebrenicia Genocide Memorial, Museum, and cemetery.

In a direct act of ethnic cleansing, over the course of a few of days in July 1995, more than 8,000 men and boys were viciously murdered, and countless women and girls raped.

It is a devastating event that is hard to put words too.

While films such as “Quo Vadis, Aida?” have mixed reviews, I am grateful for this film about Srebrenica to have been made. Unfortunately, growing up at the same time in America, it is not an event I remember learning about, and this film helped to raise my awareness.

It’s really hard to wrap my head around the fact that this horrific mass genocide happened so recently, within my lifetime. As a little girl, when I was playing soccer on the weekends, Tina was dodging sniper bullets. When I was going to summer camp, she was fleeing war being bounced to different countries, cities, family members. How does one cope with all this? How does society move on? Do they? And should they?

Before the war, Srebrenica was a majority Bosnian-Muslim town. Now it is a majority Serbian town. Looking at maps of Bosnia before the war and after, you can see how dramatically the populations have changed across the country.

In April 1993, the UN declared Srebrenica a “safe zone” to protect the local population from the Bosnian-Serb forces who created a siege around it in order. Tens of thousands of refugees, who were fleeing nearby Bosnian-Serb attacks on nearby villages’ Muslim populations, arrived at Srebrenica for safekeeping.

The UNPROFOR forces proved impotent and failed horrifically to protect the civilians.

Learn more at the Srebrenica Memorial Center: https://srebrenicamemorial.org/en

Recommended To Do in Sarajevo

- Visit the War Childhood Museum

- Visit the Tunnel Of Salvation

- Visit the Sarajevo Library / City Hall

- Take the Cable Car up to Trebevic and the Bobsled Tracks

- Visit the Siege of Sarajevo Museum

- Have a brew at WalterEgo Pub

Stephanie’s top 3 travel tips for Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Spend some time hiking in the mountains

- Dine on the national dish of Ćevapi and enjoy the cafe culture of the country

- Try to understand the complex history involving multiple ethnicities and religions and be as respectful as possible to varying points of views and social norms

Useful Links:

- Mr History’s A Super Quick History Of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Crash Course

- Lonely Planet

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/destinations/bosnia-and-hercegovina

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/outdoor-adventures-bosnia-hercegovina

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/9-ways-to-explore-bosnia-and-hercegovinas-rich-islamic-heritage

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/ten-reasons-to-visit-bosnia-hercegovina

- Britannica

- National Geographic

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destination/bosnia-herzegovina

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/bunkers-adventure-weekend-bosnia-herzegovina

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/paid-content-outdoor-adventures-herzegovina

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/explore-the-historic-herzegovina-wine-route-bosnia

- Atlas Obscura

- CIA World Factbook

- BBC Country Profile

- Wiki Travel

- About Bosnia and Herzegovina

- About Sarajevo:

Travel Blogs:

- https://www.adventureswithluda.com/bosnia-herzegovina-travel-guide/

- https://justynjen.com/traveling-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina/

- https://www.nomadicmatt.com/travel-guides/bosnia-herzegovina-travel-guide/

- https://wander-lush.org/visit-bosnia-and-herzegovina-travel-guide/

- https://www.adventurouskate.com/category/destinations/bosnia-and-herzegovina/

- https://alittleadrift.com/bosnia-herzegovina/

- https://www.bucketlistly.blog/posts/bosnia-and-herzegovina-backpacking-itinerary